Two Revolutions, Same Pattern: How Bob Moog’s Story Predicts Our AI Future

Look, I’ve spent enough time watching tech revolutions come and go to recognize a pattern when I see one. The basement and the chat window. Two inventors, sixty years apart, both trying to build “cool tools that make interesting things.” Neither realized they were about to trigger revolutions that would redefine human creativity itself.

The Basement (1963) and the Chat Window (2025)

So picture this: Bob Moog, 29 years old, hunched over breadboards in his basement workshop in Trumansburg. Oscillators, filters, voltage-controlled amplifiers scattered across workbenches like some kind of electronic poetry waiting to be assembled. This wasn’t his first rodeo with electronic gadgets. By 1961, the guy had already sold around 1,000 theremin kits for $50 each (that’s roughly $400,000 in today’s money, funding his Cornell education one spooky electronic ghost-sound at a time). (For a complete timeline of Moog’s innovations, check out the Bob Moog Foundation’s comprehensive timeline.)

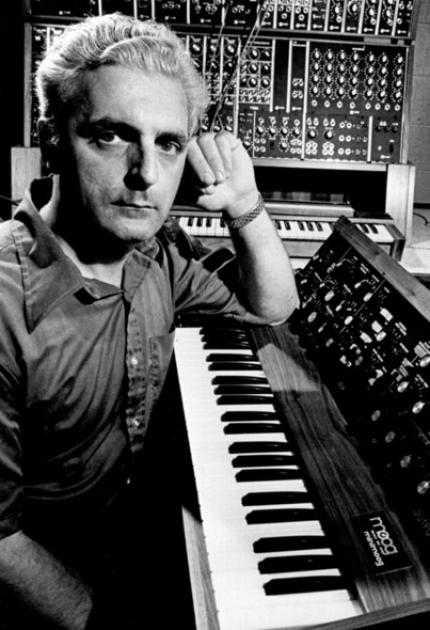

The basement workshop that changed everything: Robert Moog surrounded by the voltage-controlled oscillators, filters, and patch cables that would democratize electronic music creation

But the synthesizer was different. This was his attempt to build something genuinely revolutionary: an electronic instrument that could make sounds no acoustic instrument could produce, controlled by voltage rather than mechanical keys. This breakthrough would eventually earn him over 25 patents and completely reshape music.

When he demonstrated his modular synthesizer at trade shows, the reactions were… well, imagine showing a smartphone to someone from 1950. Classical musicians squinted at the knobs and cables: “Why would I want a machine that goes ‘BEEP BOOP’?” Rock musicians looked for familiar territory: “Where are the guitar strings?” Record executives did quick math: “Who’s going to buy a $10,000 noise machine?”

The confusion ran deeper than skepticism. These weren’t just business concerns. Musicians felt something fundamental was being challenged. Their craft. Their identity. Their very reason for existing.

Then Wendy Carlos sat down with it.

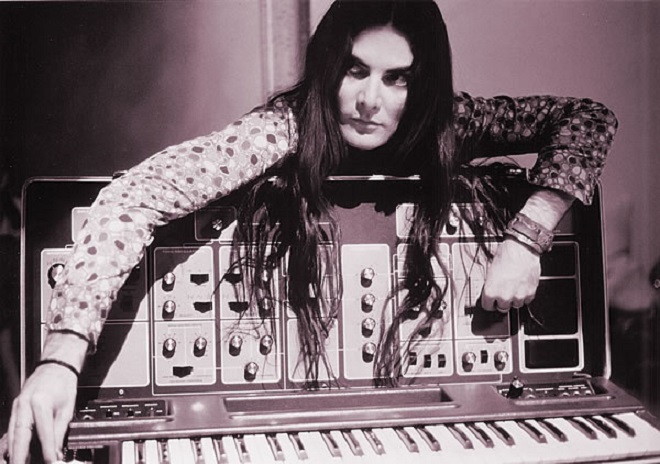

“Switched-On Bach” creator Wendy Carlos: The visionary who spent 1,100 hours proving that machines could help humans create music that touched souls, not replace them

Now here’s where it gets interesting. She wasn’t just some user trying to figure out the latest gadget. Carlos was a co-developer. After meeting Bob Moog at the 1964 Audio Engineering Society show, she started ordering custom-designed synthesizer modules and giving him extensive technical assistance. She convinced Moog to add crucial features like the touch-sensitive keyboard, portamento control, and the fixed filter bank. Moog himself credited Carlos with originating many features of his synthesizer.

Over 1,100 painstaking hours, she turned Bach’s compositions into something the world had never heard. Working 8 hours a day, five days a week, for five months while maintaining her day job as a recording engineer. Using her self-built 8-track recorder (she couldn’t afford commercial equipment), Carlos had to record every single note separately since the Moog was monophonic.

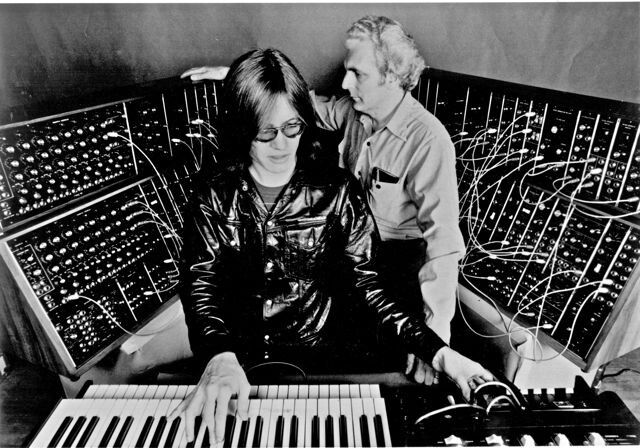

The collaboration that launched a revolution: When inventor Bob Moog partnered with composer Wendy Carlos, they didn’t just create new technology—they proved that human creativity and machine capability could amplify each other beyond what either could achieve alone

Here’s the twist that nobody saw coming: the “artificial” music made people feel more emotional, not less.

“Switched-On Bach” hit #10 on the Billboard 200, won 3 Grammy Awards in 1970, and sold over 1 million copies. Glenn Gould called it “the album of the decade.” The synthesizer wasn’t just legitimate. It was revelatory.

Fast forward to today. Picture someone (maybe you?) staring at a blank AI prompt box. They want to coordinate a complex family vacation without the usual three weeks of scheduling arguments, budget debates, and conflicting preferences. This isn’t their first experiment with AI—they’ve used it for simple tasks, written a few emails, maybe generated some ideas.

But this is different. They want to build something revolutionary: a decision-making process that could handle complexity no traditional planning method could manage, powered by algorithms rather than endless family meetings. This breakthrough is reshaping how humans think together.

When AI coordination gets demonstrated, the reactions are… well, you know the drill. Knowledge workers squint at the interface: “Why would I want a machine that writes my thoughts?” Executives look for familiar territory: “Where’s the human judgment?” Educators do quick math: “Who’s going to trust a robot with important decisions?”

The confusion runs deeper than skepticism. These aren’t just practical concerns. Knowledge workers feel something fundamental being challenged. Their expertise. Their identity. Their very reason for being valuable.

Then someone sits down with it.

They don’t fight the machine. They partner with it. They learn the intricate dance of human wisdom plus AI processing power. Every constraint recorded, every variable considered, every decision documented in seconds rather than weeks.

Here’s the twist nobody saw coming: the “artificial” thinking makes decisions more human, not less. The AI handles tedious variable-juggling, freeing humans to focus on what they do best: values, relationships, intuition, meaning.

When Musicians (and Knowledge Workers) Declared War

Look, the critics weren’t just skeptical back in the 1970s. They were fighting for their souls.

Morrissey famously declared in 1983: “there was nothing more repellent than the synthesizer.” Critics described synth-pop as “anaemic” and “soulless.” Gary Numan observed the hostility firsthand, noting how people would dismiss his work because “machines did it.” Andy McCluskey of OMD captured the dismissive attitude perfectly: people thought “the equipment wrote the song for you.”

The contempt was personal and professional. Musicians felt their craft was being reduced to button-pushing. Critics worried that emotional expression couldn’t survive electronic mediation. Union musicians didn’t just complain; they organized. Protests outside synthesizer concerts. Lobbying to ban “artificial instruments” from venues. Grammy committees held heated all-night sessions about whether electronic albums deserved to exist in the same category as “real” music.

The irony was painful. While critics debated authenticity, Bob Moog was losing control of his own company. In 1973, financial pressures forced him to rename R.A. Moog Co. to Moog Music. By 1977, poor management and marketing failures pushed him out entirely. For the better part of the 1990s, Moog legally could not market products under his own name.

Listen to what they were really saying: If machines can make music, what makes us special?

The fear had layers. Surface level: job security. Deeper down: artistic integrity. Deepest level: human identity itself. If a machine could create beauty—if its 24dB ladder filter could produce sounds that touched souls—what did that say about the nature of human creativity?

Meanwhile, something remarkable was happening in teenagers’ bedrooms. Kids who couldn’t afford violin lessons were creating symphonies with $500 Minimoogs. Over 12,000 Minimoog Model D units were manufactured between 1971 and 1981, democratizing music creation on a scale nobody had imagined.

Today? Same script, different technology.

The Atlantic warns, “AI threatens the very soul of human intelligence.” Harvard Business Review echoes the dismissal: “Real thinkers use intuition and experience, not algorithms and data.” Knowledge workers observe the hostility firsthand, noting how colleagues dismiss AI-assisted work because “the computer did it.” Critics capture the dismissive attitude perfectly: people think “the algorithm wrote the analysis for you.”

The contempt is personal and professional. Workers feel their expertise is being reduced to prompt-crafting. Academics worry that intellectual rigor can’t survive algorithmic mediation. Academic institutions don’t just complain; they organize. Boycotts of AI-generated content. Bans on AI tools in classrooms. Publishing committees hold heated sessions about whether AI-assisted writing deserves to exist in the same category as “authentic” work.

Listen to what they’re really saying: If machines can think, what makes us special?

The Accidental Revolution(s)

Here’s what cracks me up about both revolutions: neither inventor saw them coming.

Bob Moog thought he was building sophisticated tools for professional composers and recording studios. He had visions of symphonic applications, academic research, maybe some experimental jazz.

The universe had other plans.

The real revolution happened in places Moog never expected. Kraftwerk turned mechanical precision into something that felt deeply human. Giorgio Moroder created disco with a Moog bass line that echoed through house music, hip-hop, and electronic dance music for decades. Gary Numan discovered he could “sing” through machines, creating emotional expression that transcended the human voice. Vangelis crafted impossible movie soundtracks that made audiences believe in futures they’d never imagined.

Wendy Carlos herself went beyond Bach, contributing scores to Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” (1971) and “The Shining” (1980), as well as Disney’s “Tron” (1982), cementing the Moog’s place in popular culture.

Watch the pattern: Technology didn’t replace existing music. It enhanced music while birthing entirely new forms that couldn’t exist any other way.

Today, AI companies think they’re building tools for corporations and researchers. They have visions of enterprise applications, academic research, maybe some customer service optimization.

The universe has other plans.

The real revolution is happening in places AI developers never expected. Context.bet turns weeks-long family negotiations into seconds of collaborative decision-making. Indie creators use AI collaboration to produce works of impossible scope and sophistication. Students get tutoring tailored to their exact learning gaps. Small teams achieve what once required armies of specialists.

Watch the pattern: Technology isn’t replacing existing thinking. It’s enhancing thinking while birthing entirely new forms of human-AI collaboration that couldn’t exist any other way.

What Both Revolutions Are Really About

Here’s what both revolutions are really about: distributed creativity.

Moog made it possible for musical ideas to exist independent of traditional instruments and classical training. A melody could live in voltage-controlled oscillators and exponential keyboards as naturally as in violins. His patents on electronic filters, signal generators, and dynamically responsive keyboards democratized not just music-making, but music-imagining. Suddenly, musical expression belonged to anyone with curiosity and a few hundred dollars.

AI makes it possible for cognitive insights to exist independent of individual brains and traditional expertise. A decision framework can live in algorithms as naturally as in executive experience. Suddenly, intellectual capability belongs to anyone with curiosity and an internet connection.

The beautiful irony? Both revolutions were complete accidents. Moog started by building and selling theremins with his father in 1954—electronic instruments that played with hand gestures through electromagnetic fields. AI researchers were trying to understand intelligence itself, pouring decades of work across neuroscience, mathematics, and computer science into modeling how minds work. Neither group realized they were reshaping human potential itself.

But here’s the deeper magic: Every breakthrough tool forces us to redefine what makes us uniquely human. And the answer, both times, surprises everyone.

You become more yourself, not less.

The Comeback Kid

The most hopeful part of Moog’s story isn’t his initial success—it’s his comeback. After losing his company in 1977, he spent decades in the wilderness, founding Big Briar to focus on theremins and later developing Moogerfoogers analog effects pedals.

Finally, in 2002, the Moog name and its rights were given back to their original owner after a large legal battle. With the rights back in his hands, Moog created the Minimoog Voyager—a modern interpretation of the original Model D that replicated its functionality but with numerous enhancements.

The lesson? Revolutionary tools face setbacks, corporate politics, and periods in the wilderness. But fundamental breakthroughs in human capability always find their way back.

The Campsite Principle

Here’s what both revolutions teach us: Technological change is messy, disruptive, and inevitably unfair to some people. Bob Moog didn’t pretend otherwise. But he demonstrated something crucial about how to navigate these transitions.

The Boy Scout rule applies to innovation: leave the campsite cleaner than you found it. Don’t just build cool technology. Build technology that creates more opportunities than it destroys. Don’t just solve your own problems. Solve problems for people who couldn’t solve them before.

Moog could have built synthesizers exclusively for wealthy studios and professional composers. Instead, he drove down costs and made them accessible to teenagers in bedrooms. The result wasn’t just personal success. It was an explosion of human creativity that benefited everyone.

The AI revolution offers the same choice. We can build systems that simply replace human workers, leaving a smaller pie for everyone to fight over. Or we can build systems that expand what’s possible, creating new forms of human capability that didn’t exist before.

The synthesizer taught machines to sing. AI is teaching them to think. In both cases, the breakthrough isn’t what the machines can do. The breakthrough is what they help humans become.

The Echo Across Time

Bob Moog passed away in 2005 at age 71 from an inoperable brain tumor, but his revolution echoes in every electronic beat, every synthesized melody, every bedroom producer who creates symphonies on a laptop. The Bob Moog Foundation continues his work of innovating electronic music, honoring the legacy of this humble visionary who changed the world. He proved something profound: the future of human expression doesn’t require choosing between authentic tradition and artificial innovation. The magic happens when human creativity partners with powerful tools.

As we stand at the threshold of the AI revolution, Moog’s story offers both prophecy and comfort. Yes, the skeptics will rage about authenticity. Yes, the establishment will resist democratization. But in basements and bedrooms, coffee shops and living rooms, the real revolution will quietly unfold.

Because here’s what history teaches us: The most profound technological breakthroughs don’t diminish human potential. They amplify it beyond what anyone thought possible.

The synthesizer taught machines to sing. AI is teaching them to think. And in both cases, the real breakthrough isn’t what the machines can do.

The real breakthrough is what they help humans become. 🌟

Experience the legendary Moog Model D synthesizer at context.bet/synth/model-d, and see how AI coordination transforms family decisions at context.bet/blog/family-decision-ai-coordination.